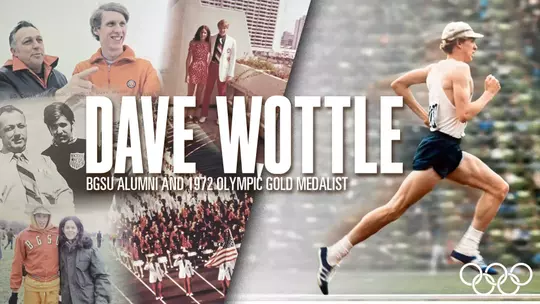

In the Nest: Olympic Spotlight with Dave Wottle

by Noah Tylutki, BGSU Strategic Communications Coordinator

7/30/2024

As the 2024 Summer Olympics begin in Paris, the story of Bowling Green great Dave Wottle’s 800m gold medal, come-from-behind performance at the 1972 Summer Olympics still inspires many. Fifty-two years later, Wottle reflects on the people and moments at Bowling Green that helped inspire him to believe in himself and achieve what he never thought was possible.

My decision to go to Bowling Green changed my life.Dave Wottle

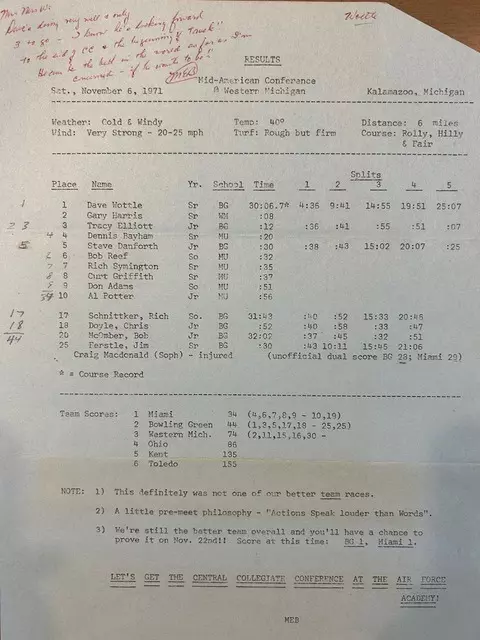

The results sheet read that Dave Wottle had won the 1971 Mid-American Conference championship in cross country with a six-mile race time of 30:06.7, which marked the Western Michigan course record. As a team, Bowling Green finished the MAC Championships in second place. Head cross country/track coach Mel Brodt typed a message at the bottom of the results page – “Actions speak louder than words.”

Brodt wrote another more personalized note in the sheet’s upper left-hand corner. Written in cursive in red ink and addressed to Wottle’s parents as an update to how the cross-country season was going, it read:

“Dave’s doing very well with only three [cross country meets] to go,” it said. “I know he is looking forward to the end of CC [cross country] and the beginning of track. He can be the best in the world as far as I am concerned – if he wants to be!”

Ten months later, he became the 800m gold medalist in the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, Germany and the last American man to win the event. Yet, it was that letter that solidified his want and desire to be the greatest in the world and helped him author one of the most memorable moments in Olympic history.

“I can remember reading (the letter), and it really set my hopes higher,” Wottle said. “If my coach believed I could be the best in the world, I should sure believe that too. That was the kind of coach he was. He believed in me more than I believed in myself.”

Brodt was recognized as “one of the leading U.S. authorities in track and cross country running” since he took over the running programs at Bowling Green in 1960. Five years later, he became the first coach to write Wottle a recruiting letter, who was only a freshman at Lincoln High School in Canton, Ohio and had only started the sport that year. Brodt even invited Wottle and his parents to come to Bowling Green for a recruiting visit, which they did.

By the time Wottle was a senior, he had slowly progressed to becoming one of the best middle-distance runners in Ohio, cumulating with a state championship in the mile. He was set on running for legendary coach Jim Wuske at the University of Mount Union in nearby Alliance, Ohio. Then, he got a call from Brodt a few weeks before classes began asking him to come to Bowling Green for another visit.

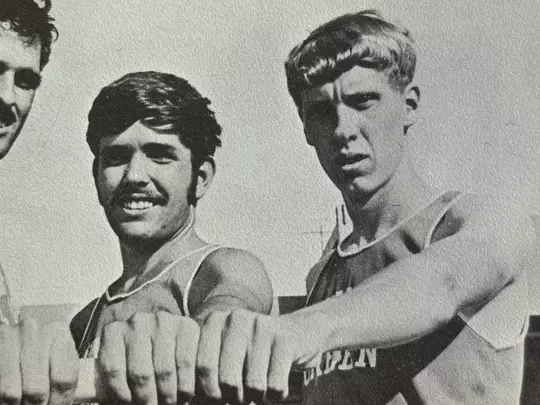

He asked eventual three-time national champion and American steeplechase record holder Sid Sink to help re-sell the school to Wottle.

“Sid was the leader of the team and was doggone famous,” Wottle said. “When he talked to me, he got me so excited about the potential of BG competing at the national level and it changed my mind. I felt that Sid would push me as a runner with his national aspirations. I still do not think that he gets the recognition that he should.”

Wottle was someone who needed to be pushed. Considering himself an introvert, he never possessed leadership skills as a runner and could not motivate like Sink could. He was extremely comfortable with playing the role of the follower, one that required a few words and more action.

Sid [Sink] was the leader of the team and was doggone famous. When he talked to me, he got me so excited about the potential of BG competing at the national level and it changed my mind. I felt that Sid would push me as a runner with his national aspirations. I still do not think that he gets the recognition that he should.Dave Wottle

Over the next two years, Wottle continued to develop under Brodt’s tutelage and Sink’s leadership. He trusted Brodt with his training regiments and completed every workout that he designed for him, never questioning the former member of the World War II Army Air Corps. In 1970, Wottle earned his first All-America honor by finishing fourth in the mile at the NCAA Indoor Championships. He followed it up with a runner-up performance to No. 1 miler in the world Marty Liquori by a mere 0.2 seconds at the NCAA Outdoor Championships.

“That closeness in that mile was what first gave me an inkling that I could compete with the best in the world,” Wottle said.

With his confidence sky high and a feeling that he could take on the world, Wottle entered the 1970 fall cross country season with his sights on achieving even more.

But his career almost took a turn for the worse.

Before the MAC Championships, he developed a stress fracture in his left fibula that kept him sidelined for six weeks. Trying to gear up for the indoor track season, he developed bursitis in his left knee which sidelined him for five weeks. Then, another stress fracture occurred – this time in his right fibula. Shortly after, injury ruled him out for the entire 1971 indoor/outdoor track seasons.

Rooming with Sink during this time did not make the circumstance any better. Wottle watched him run during the peak of his career, as he won individual titles at the NCAA Indoor and Outdoor Championships while setting the American record in the steeplechase at the Pan-American Games that summer.

“It was a very depressing time in my career,” Wottle said. “I saw all of his success and wanted to run, but I couldn’t run.”

Through the whirlwind of emotions, Wottle met his future wife Jan in January of 1971. He knew of her because she had dated some other runners on the team in the past. After the first date – watching the Alfred Hitchcock horror film Psycho – he was hooked. They married a year and a half later.

“She gave me a tremendous boost of confidence,” Wottle said. “She helped me through that dark period because I had something that I was excited about. I fell in love, and it was a tremendous help during that time.”

Wottle now had a burning desire to perform and even more of a passion to achieve greatness once he recovered from his injuries. Following Brodt’s workouts, he ran 70-85 miles a week to build up his leg strength when most middle-distance runners would run 40-60 in that span during training. After staying healthy throughout the season, Wottle won his first-career individual national title in the 1500m at the 1972 NCAA Outdoor Championships.

With Olympic aspirations for that summer, Brodt entered Wottle into the event at the USA Outdoor Track and Field Championships organized by the Amateur Athletic Association held at the University of Washington. However, it was having Wottle also compete in the 800m at the Championships that allowed him to begin his path into Olympic lore.

Brodt’s intent in Wottle running the 800m was to use it as a speed workout to prepare for the 1500m race later that week. The results of the 800m equally stunned both.

Wottle ended up winning the 800m, which qualified him for the Olympic trials. He also used that momentum to qualify in the 1500m, which was the original plan all along.

Then, just two weeks later, Wottle did the unthinkable by excelling in the 800m enough to tie the world record at Olympic trials at Hayward Field in Eugene, Oregon with a 1:44.3 mark and dropping an unprecedented three seconds off his time from the USA Championships. Sink, who was at the trials competing in the steeplechase and 5000m despite fighting a sciatic injury, was the first to greet him on the track.

“It was an absolute shock to Coach Brodt and myself that I would be competing in the Olympics in the 800m,” Wottle said. “I always ran the mile (1500m), and I never thought I had enough speed to be a half-miler (800m). If you said the 1500m, it would be different. My goal was to win the 1500m, but after I tied the world record, I was smart enough to know I needed to reevaluate the gold and go back to running the 800m.”

A newly-married Wottle had his eyes set on a new goal now – winning the 800m in Munich. Coming in with the world’s fastest time, he had the confidence he could come away victorious. However, during the first day of a week-long U.S. Track & Field training session at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine just five days after Wottle and Jan got married, he started to develop tendinitis in his left knee. It came after a hard workout trying to prove himself to U.S. Track & Field coach Bill Bowerman, who was publicly outspoken about Wottle’s decision to get married so close to the date of the Olympics. His injury limited his workouts to just light jogs for a few miles leading up to Munich.

As the Olympics started, Wottle estimated that his conditioning was at 85-90 percent of what he was at the Olympic trials due to his inability to exercise properly. He was pushing through his tendinitis, and slowly it did not start affecting him by the time he started racing.

Wottle survived and advanced through the prelims and semifinals which placed him in the Olympic finals and set him up for one of the most memorable races in Olympic history.

“Before the gun went off, I felt that I could win,” Wottle remembered on that beautiful, 75-degree day. “Once the gun went off, I had my doubts.”

“It was an absolute shock to Coach Brodt and myself that I would be competing in the Olympics in the 800m. I always ran the mile (1500m), and I never thought I had enough speed to be a half-miler (800m). If you said the 1500m, it would be different. My goal was to win the 1500m, but after I tied the world record, I was smart enough to know I needed to reevaluate the gold and go back to running the 800m.Dave Wottle

Just like in his previous 800m races, Wottle tactically planned to stay in the back of the pack and stay out of trouble before making a move in the homestretch. The race started out at a quick pace, and he fell behind by about 10 meters. The more he fell behind, the more he felt embarrassed and panicked, thinking of how his family and friends felt seeing him falter on a worldwide stage.

In the race's second 200m leg, the pack slowed down, enabling Wottle to catch up. As he started the second lap, he thought to himself, ‘I can do this.’

But Wottle would have to snap out of his comfort because the world’s No. 1 800m runner, Yevhen Arzhanov from the USSR, sped up and made his move. Wottle was not ready to progress yet but stayed on the outside. Then, with about 170 meters to go, he set his kick in and began passing other runners.

After surpassing Kenya’s Mike Boit with about 15 meters left, all he had left was to pass Arzhanov.

“Once I passed Boit, I thought I might have a shot at the gold medal,” Wottle recalled. “It was only a couple meters from the finish line that it looked like I realistically had a chance to get Arzhanov.”

As Arzhanov faltered at the end of the race causing him to dive forward, Wottle leaned at the finish line, but it was too close to call. He could only wait for the official results to flash on the scoreboard above Olympic Stadium.

Wottle looked dazed. Liquori, who had been a guest commentator for ABC alongside legendary broadcaster Jim McKay, said on air, “I think Dave is stunned. I do not think he realizes what he has just done.”

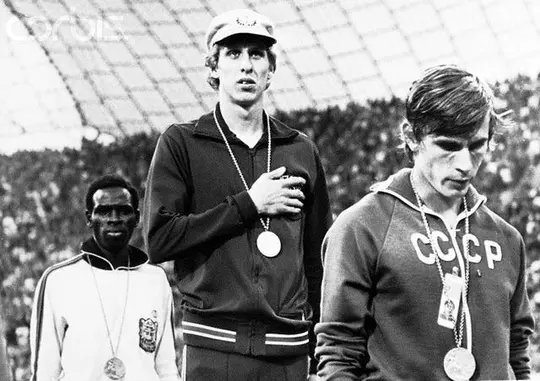

The first name to appear on the scoreboard was “Wottle, D; USA: 1:45.86,” and it showed he had beaten Arzhanov by a mere 0.03 seconds.

“It was tremendously exciting,” said Wottle, recalling the astonishing moment. “I was not an overly emotional person and one to jump around and scream, but inside it was taking effect. It was a cool feeling.”

The feeling carried over to the medal ceremony, where he was so stunned at what just happened that he forgot to remove his trademark golf hat he wore during races during the United States national anthem.

Bowling Green was also excited for Wottle, who returned to his stomping grounds to a parade down Main Street in a float with Jan and his parents. Later that fall, he began student teaching to finish his education degree which allowed him to stay humble and from “getting too big of a head.”

After competing in his final year of eligibility in indoor/outdoor track, Wottle competed in professional track for two years but never fit his style.

“It wasn’t a good match for me,” Wottle said. “My personality as a follower was not conducive to running in pro track and having to train by myself with no team or leader like Sid. I could not push myself hard enough to do well.”

Later in life, the follower took on more leadership roles after gaining more self-confidence. While running pro track, he founded the track program at Walsh University near his hometown of Canton and served as admissions director. Later, he coached at Bethany College in West Virginia after an admissions job opened. That eventually led him to Rhodes College, a Division III school in Memphis, Tenn., where he served as Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid for 28 years.

Today, Wottle enjoys his retirement from Memphis with Jan. He also comes up to Bowling Green from time to time and enjoys seeing his teammates who are “like brothers” to him. Over the years, Wottle has spoken in front of dozens of groups to share his story of chasing Olympic gold which is one way he credits building more self-confidence.

But the actions of others at Bowling Green – not words – are what pushed Wottle to become the best in the world.

“My decision to go to Bowling Green changed my life,” Wottle said. “I do not think any other school I could have gone to would have been the right fit for my personality – my teammates, Sid Sink and Coach Brodt being there made all the difference in the world for me. I am wise enough to know that what I achieved was a direct result to what they did for me.”